Waukegan, There I Come From

Ray Bradbury, science fiction master and native of my hometown (immortalized as Green Town in his classic Dandelion Wine) once wrote a poem, a hymn rather, an homage to Waukegan, Illinois. The line, lodged forever in my brain at seventeen, "Waukegan, There I come from, and not, my friends, Byzantium" has become a dizzy undercurrent of my daily thought pattern. I will admit that the poem itself causes me to shudder, even this line which I can no more erase from my thought waves, but it has become a part of me, and so has Waukegan and so has Ray. (All right, I've never met Ray, but his nephew did play tuba in the high school orchestra at the same time as I did.)

Decades later, I am sitting in the Swedish equivalent of a bistro, located just off Odengatan (the old gods were big with the Stockholm city planners a hundred-odd years ago). Swedish author Niklas Rådström is sitting across the table and we are talking literature, translation, and my recent translations of his poems. It was the first time we had met face-to-face, and it felt a bit odd for me, as I was a total newcomer to the translation scene and Rådström's reputation was well-established in Sweden. Then I asked about the writer who had influenced him most when he was starting out, and he said, to my surprise, "Ray Bradbury."

"Ray Bradbury? He's from my hometown."

"Really? I don't believe it. My translator comes from Bradbury's hometown! Bradbury should win the Nobel Prize. His prose is beautiful, so poetic."

"Though his poetry, well..." I said, and then quoted the quote that rattles my brain.

We went back and forth on Bradbury's novels, returning to Dandelion Wine.

"That one, I think, influenced my writing the most in the beginning," said Niklas. "When I was a teenager."

"Your trilogy does remind me of his work," I said. "The poetic and the scientific combined in a memoir, minus some of the more science-fictiony aspects."

As I left the bisto, I wondered. Did Rådström like my translations of his poetry because Ray and I spoke the same Waukegani dialect, and this way of thinking, this way of writing words in a string until the prose becomes poetry is as much a part of my molecular system as the water of Lake Michigan? Or was I drawn to translate Rådström's work because he had created a Swedish way of writing Waukegani-style?

I know one thing: Bradbury loved Waukegan with a passion that he would not hide, and Rådström also loves Stockholm, loves its bistros, its neon, its building facades, its birds and trees and the people who inhabit its cinemas and restaurants.

It's the love, the thing that matters most in art. Without it, style be damned.

Waukegan, there I come from....

Friday, December 30, 2005

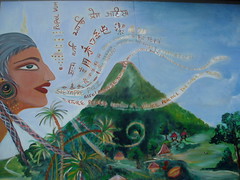

Mural, San Francisco

This mural is at 24th and Valencia in the Mission District of San Francisco... the photo is of a detail from it.

It's by Marta Ayala, and is called "Roots and frequencies basic to our education".

It's by Marta Ayala, and is called "Roots and frequencies basic to our education".

Friday, December 23, 2005

Imaginary translations

I'm curious to take a look at "Imaginary Poets", an anthology of translations of made-up poets. It's 20 well-known poets, each asked to make up a poet, translate the poem to English, and write an essay about the poet and their work.

It's a fun and playful idea. I tend to like that sort of thing. I liked that book that was a fake translation of an imaginary ancient Greek poet. I love things like "Songs of Bilitis" by Pierre Louys - I even love Ossian and that whole strange cult of Ossian. Flat-out parodies charm me immensely...

And yet I find that the idea of project at this particular moment in our country's history makes me sad and angry. If I felt that people in this country knew anything substantial about non-US cultures, history, or other languages, maybe I'd be less pissed off. I think of all the excellent poets, dead or alive, who are NOT translated or well-known even in literary communities in the U.S. Great - we're so ignorant about other cultures and languages and poets, we think we get to invent them and make them up. I'd be embarrassed to make up a fake Latin American poet. If I were going to do that kind of project, I'd do it in the context of science fiction or speculative fiction, and would make up a completely alien culture, and I'd do it to make some interesting political point; this distancing allows for a lot of play and exploration... Science fiction writers use alien races to explore ideas of race, class, gender, and utopia - all the time in the U.S. today.

There is at least room for some thought and questioning, some room to be conflicted about art, poetics, humor, and politics.

I'm sure many of the people who contributed to Imaginary Poets considered issues of cultural imperialism and cultural appropriation. There's some excellent and thoughtful translators in the table of contents. I'm very curious to see the book and see what they did with the idea. Will I be so charmed by the book's witty cosmopolitan sophistication that I won't care about the cultural politics? Or will I just be more embarrassed than I am now? I'll read it and report back.

It's a fun and playful idea. I tend to like that sort of thing. I liked that book that was a fake translation of an imaginary ancient Greek poet. I love things like "Songs of Bilitis" by Pierre Louys - I even love Ossian and that whole strange cult of Ossian. Flat-out parodies charm me immensely...

And yet I find that the idea of project at this particular moment in our country's history makes me sad and angry. If I felt that people in this country knew anything substantial about non-US cultures, history, or other languages, maybe I'd be less pissed off. I think of all the excellent poets, dead or alive, who are NOT translated or well-known even in literary communities in the U.S. Great - we're so ignorant about other cultures and languages and poets, we think we get to invent them and make them up. I'd be embarrassed to make up a fake Latin American poet. If I were going to do that kind of project, I'd do it in the context of science fiction or speculative fiction, and would make up a completely alien culture, and I'd do it to make some interesting political point; this distancing allows for a lot of play and exploration... Science fiction writers use alien races to explore ideas of race, class, gender, and utopia - all the time in the U.S. today.

There is at least room for some thought and questioning, some room to be conflicted about art, poetics, humor, and politics.

I'm sure many of the people who contributed to Imaginary Poets considered issues of cultural imperialism and cultural appropriation. There's some excellent and thoughtful translators in the table of contents. I'm very curious to see the book and see what they did with the idea. Will I be so charmed by the book's witty cosmopolitan sophistication that I won't care about the cultural politics? Or will I just be more embarrassed than I am now? I'll read it and report back.

Thursday, December 22, 2005

Slavic women's translation registry

The Association for Women in Slavic Studies has announced that the expanded and updated AWSS Translation Registry is now online at:http://www.awsshome.org/resources/registry.html

The Registry includes both published translations of work by women authors and translations in progress from a wide variety of Slavic and East European languages. The data base can be searched in a variety of ways, making it a valuable resource for teaching, research, and planning future translations or anthologies.

You may direct questions, suggestions or updates to Sibelan Forrester <sforres1@swarthmore.edu>) or Diana Greene <diana.greene@nyu.edu>.

The Registry includes both published translations of work by women authors and translations in progress from a wide variety of Slavic and East European languages. The data base can be searched in a variety of ways, making it a valuable resource for teaching, research, and planning future translations or anthologies.

You may direct questions, suggestions or updates to Sibelan Forrester <sforres1@swarthmore.edu>) or Diana Greene <diana.greene@nyu.edu>.

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

A link to Langwich Sandwich

Langwich Sandwich

Wow! This page is a dynamic aggregator of many language and translation blogs.

The titles of recent posts from a blog, for example Languagehat, show up here as links. If you mouseover the link, you'll see the first few lines of its content. Very handy. It's a great starting point to see the best of the language and translation blogs!

Wow! This page is a dynamic aggregator of many language and translation blogs.

The titles of recent posts from a blog, for example Languagehat, show up here as links. If you mouseover the link, you'll see the first few lines of its content. Very handy. It's a great starting point to see the best of the language and translation blogs!

Monday, December 19, 2005

Baudelaire & Rimbaud

What a lovely surprise I got today in the mail from Eric Greinke: two beautiful chapbooks from Presa Press: The Rebel: Poems by Charles Baudelaire / American Versions by Leslie H. Whitten Jr, and The Drunken Boat & Other Poems from the French of Arthur Rimbaud / American Versions by Eric Greinke.

For fun, here's a random line from the latter:

A white ray tumbles above the clouds & brings an abrupt

end to this merciless comedy

For fun, here's a random line from the latter:

A white ray tumbles above the clouds & brings an abrupt

end to this merciless comedy

Saturday, December 17, 2005

update on Nadia Anjuman

Nadia Anjuman died earlier this year, and the international attention to her story created some demand for translations of her work. I still dont' know if anyone is working on translating her book into English or other languages. Someone passed on this page about her, from Bukhara: Review of Arts, Culture, and Humanities.

Here's an update from the writer Ren Powell:

Here's an update from the writer Ren Powell:

The Norwegian PEN center together with Centre Culturel Francais plan to support a PEN Writer's House Publishing in Kabul. It will be a cooperative venture with the existing publishing house Maiwand .

The three groups will finance printing, distribution and a royal for writers, while an Afghan PEN subcommittee will choose the manuscripts. The first book is expected in January next year (I'm not sure if this is 06 or 07). According to the report on Norwegian PEN's website, the first book will most likely be a collection by Anjuman. This will be in Farsi, of course.

Friday, December 16, 2005

The Dangers of Double Translation

I believe there's a standard term for translating through an intermediate language, a practice necessitated by the dearth of qualified translators from Chinese, Arabic, and other minor languages, but for the time being I'll call it double translation.

Case in point, The Girl Who Played Go, by Shan Sa, and translated into English from the French. (I'll leave the French translator unnamed.) An episode in the book involves Japanese soldiers fighting in Manchuria on the border with Russia. I don't mind them calling the city "Ha Rebin" (what we know as Harbin), but the very long river that separates the two countries is referred to repeatedly as "River Love."

There's never a good copy editor in the house when you need one.

Case in point, The Girl Who Played Go, by Shan Sa, and translated into English from the French. (I'll leave the French translator unnamed.) An episode in the book involves Japanese soldiers fighting in Manchuria on the border with Russia. I don't mind them calling the city "Ha Rebin" (what we know as Harbin), but the very long river that separates the two countries is referred to repeatedly as "River Love."

There's never a good copy editor in the house when you need one.

Friday, December 09, 2005

It's like, la lengua de Cervantes

Spanish at school translates to suspension

The tension in Kansas City over a teenager's suspension from school for speaking Spanish on campus reflects a broader national debate over the language Americans should speak amid a wave of Hispanic immigration.

In today's Washington Post

The tension in Kansas City over a teenager's suspension from school for speaking Spanish on campus reflects a broader national debate over the language Americans should speak amid a wave of Hispanic immigration.

In today's Washington Post

Catalog of Copyright Entries

Jeffrey S. Ankrom, an ALTA member and copyright attorney, passed us this excellent, useful link to a site on the Catalog of Copyright Entries. I especially recommend this section on how to determine if a copyright has been renewed.

Ankrom sent us a detailed "short version" of his process in figuring out the copyright status of All Quiet on the Western Front.

International copyright is very confusing. At least this CCE might give a starting point to some people!

Ankrom sent us a detailed "short version" of his process in figuring out the copyright status of All Quiet on the Western Front.

International copyright is very confusing. At least this CCE might give a starting point to some people!

Monday, December 05, 2005

Recent reading: Native Tongue

Translators are key in Suzette Haden Elgin's dystopian classic from 1983, Native Tongue. It's 2182. Earth's economy depends on fluency in alien languages, and the only way to be fluent is to be born a Linguist, and grow up from infancy with an Alien In Residence. The Linguists are a class apart, living in austerity, working terribly long hours, the target of human resentment because they can't have babies and train them fast enough to be interpreters.

Part of the result of this situation is a patriarchal dystopia similar to Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale (1986) in which women have very few rights. The book's central premise is the women's invention of a secret language, their attempt to reshape reality through language.

Alien literary translation enters into the story briefly, when Nazareth, a brilliant young linguist, has offended alien trade negotiators for the umpteenth time. In order to understand just how she has transgressed the bounds of politeness, she tells a long rambling story gently introducing the offensive ideas (in this case, color) to gauge the alien reaction without triggering their hostile withdrawal.

Haden Elgin has a fascinating blog. She talks about linguistics, teaching, poetry, science fiction, feminism; lately she's told some autobiographical stories that have a bearing on translation. In her early life she went to Europe to life with her husband's family, and she writes eloquently of the cultural and gender boundaries she transgressed and how difficult it was to figure out through interpretation of social and nonverbal cues what she was doing "wrong".

Part of the result of this situation is a patriarchal dystopia similar to Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale (1986) in which women have very few rights. The book's central premise is the women's invention of a secret language, their attempt to reshape reality through language.

Alien literary translation enters into the story briefly, when Nazareth, a brilliant young linguist, has offended alien trade negotiators for the umpteenth time. In order to understand just how she has transgressed the bounds of politeness, she tells a long rambling story gently introducing the offensive ideas (in this case, color) to gauge the alien reaction without triggering their hostile withdrawal.

Haden Elgin has a fascinating blog. She talks about linguistics, teaching, poetry, science fiction, feminism; lately she's told some autobiographical stories that have a bearing on translation. In her early life she went to Europe to life with her husband's family, and she writes eloquently of the cultural and gender boundaries she transgressed and how difficult it was to figure out through interpretation of social and nonverbal cues what she was doing "wrong".

Friday, December 02, 2005

Why I decided to be ALTA 2006 Host Chair

Lately, I've found myself considering translators and their role in transfering and promoting the literature of the language that they translate. One reason for this is that I am the host chair for ALTA's 2006 annual meeting, and, although the official invitation in the newsletter has not yet been published, the first proposals have started to cross my desk. I am amazed by the creativity of these early proposals and am eagerly looking forward to the rush prior to the deadline cutoff of April 3rd. And I also realize how grateful I am to other translators, and the way that they have brought the rest of the world to me through their difficult, creative work.

We all know that translation cannot be the source text, no matter how hard we try. And yet, in the hope of showing our fellow English-speaking members of Planet Earth that our language has much to offer humanity, we work on with our dreams and dictionaries, hoping to bring forth an artistic creation worthy of the text that we have in our hands. And much as we wish that we could read everything in the original, this is just not humanly possible short of brain implants. I can read fluent Swedish, Norwegian, Danish and German, and prefer to read works in those languages and not in translation. In Montreal, I picked up a number of novels in Quebecois, since I do read (though would never dare to translate) French. But in spite of the rise of Hispanic culture and language in the USA, I have never learned to speak or read Spanish, and must trust my translator to convey the text to me. I certainly don't speak Vietnamese, and now that I have an exchange student living in my house from Vietnam, I turned to Vietnamese literature in translated into English to find out about my guest student's culture and background. I was saddened to see how little of Vietnamese literature was presently available, and treasured every work I got my hands on. And how many of us in North America speak Mandarin Chinese? I've been working on learning Chinese, but assume that it will be a good five years before I can read a simple text. Again, my collection of Chinese literature is all in translation.

The events in the Middle East have brought a renewed interest in fiction and memoirs from the countries of the region, and, if you are like me and do not speak Arabic, Persian or Hebrew, it is the work of translators which allows us to experience these works and to inform our understanding of that corner of our planet. But how important that we do read these texts and understand as much as possible about the world they describe!

Literary translators have a hard lot. No matter how much they have polished their translations, no matter how many years they have devoted to the text, they are rewarded by criticism at best, dismissal or invisibility most of the time, and let's not even mention the abysmal financial renumeration in these United States. The legal or medical translator may be anonymous, but at least that person is well-paid, relatively speaking, for his/her work. We literary translators are also contributing to society. I am looking forward to planning (with the quite able and vocal help of the rest of the committee) ALTA 2006 in order to give my fellow literary translators that place to be heard and appreciated. My time is my gift to you and your hard, and (so neccessary in this world) chosen profession.

And now, let's see what the day's e-mail has brought in for 2006!

We all know that translation cannot be the source text, no matter how hard we try. And yet, in the hope of showing our fellow English-speaking members of Planet Earth that our language has much to offer humanity, we work on with our dreams and dictionaries, hoping to bring forth an artistic creation worthy of the text that we have in our hands. And much as we wish that we could read everything in the original, this is just not humanly possible short of brain implants. I can read fluent Swedish, Norwegian, Danish and German, and prefer to read works in those languages and not in translation. In Montreal, I picked up a number of novels in Quebecois, since I do read (though would never dare to translate) French. But in spite of the rise of Hispanic culture and language in the USA, I have never learned to speak or read Spanish, and must trust my translator to convey the text to me. I certainly don't speak Vietnamese, and now that I have an exchange student living in my house from Vietnam, I turned to Vietnamese literature in translated into English to find out about my guest student's culture and background. I was saddened to see how little of Vietnamese literature was presently available, and treasured every work I got my hands on. And how many of us in North America speak Mandarin Chinese? I've been working on learning Chinese, but assume that it will be a good five years before I can read a simple text. Again, my collection of Chinese literature is all in translation.

The events in the Middle East have brought a renewed interest in fiction and memoirs from the countries of the region, and, if you are like me and do not speak Arabic, Persian or Hebrew, it is the work of translators which allows us to experience these works and to inform our understanding of that corner of our planet. But how important that we do read these texts and understand as much as possible about the world they describe!

Literary translators have a hard lot. No matter how much they have polished their translations, no matter how many years they have devoted to the text, they are rewarded by criticism at best, dismissal or invisibility most of the time, and let's not even mention the abysmal financial renumeration in these United States. The legal or medical translator may be anonymous, but at least that person is well-paid, relatively speaking, for his/her work. We literary translators are also contributing to society. I am looking forward to planning (with the quite able and vocal help of the rest of the committee) ALTA 2006 in order to give my fellow literary translators that place to be heard and appreciated. My time is my gift to you and your hard, and (so neccessary in this world) chosen profession.

And now, let's see what the day's e-mail has brought in for 2006!

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Radio show on Bible translations

Here's a recent recorded radio show that translators might find interesting: KQED program on translations of the Bible. The show aired Wed, Nov 30, 2005 -- 9:00 AM. You may need to scroll down the page to find that specific program description and the link to listen to it from your computer.

Thanks to Mark Pritchard for the link!

Translating Sacred Texts

Michael Krasny and guests discuss the challenges of translating the bible and other sacred texts.

Host: Michael Krasny

Guests:

Chana Bloch, poet, translator, professor of English and director of the Creative Writing Program at Mills College

Naomi Sheindel Seidman, Koret Professor of Jewish Culture and director of the Richard S. Dinner Center for Jewish Studies at the Graduate Theological Union

Robert Alter, Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature at UC Berkeley and author of many books on the Bible and Hebrew literature, including "The Art of Biblical Narrative," "The Art of Biblical Poetry" and his recent translation, "The Five Books of Moses"

Thanks to Mark Pritchard for the link!

Composite #2, get it while it's hot

I'm mailing out copies of Composite #2. It's a small xeroxed zine, featuring one poem, "Fusión" in Spanish, with 14 different translations of that poem into English, German, and French. If you'd like a copy, email me at editor (at) compositetranslation.com, and I'll mail you one. Printing costs and postage are very cheap, since it's small and I'm xeroxing.

At the ALTA conference I gave away about 30 and sold 30 more. I give 5-10 copies to contributors so they can distribute it to people who are interested in translation. In fact, I sent extra copies to past contributors too. Other than that, they get distributed at poetry readings. Sometimes I charge two dollars, hoping that I'll break even. But the idea is just to have it be cheap enough so that I can give it away. I got rid of over 400 copies of the first issue! To good homes! Not to bookstores where they molder forever or get thrown away. Though it's cheaply produced, I think the zine comes out looking nice enough that people want to keep it for its physicality as well as for the ideas.

Actually - at the conference some people asked for 20 copies so they could use it for their classes. I lost my notebook in the conference hotel, and have forgotten who wanted the extra copies. Email me a reminder if you see this post.

One more thing about my little magazine - I would love more suggestions for future poems from any language. It should be relatively short because of the magazine's tiny format. It should be something that you can imagine being translated many different ways into English. And since I don't know every language, I need guest editors to take a look at the quality of submissions! It also helps if the poem is public domain though I don't want to make it a requirement. Put suggestions here in the comments or email them to me!

At the ALTA conference I gave away about 30 and sold 30 more. I give 5-10 copies to contributors so they can distribute it to people who are interested in translation. In fact, I sent extra copies to past contributors too. Other than that, they get distributed at poetry readings. Sometimes I charge two dollars, hoping that I'll break even. But the idea is just to have it be cheap enough so that I can give it away. I got rid of over 400 copies of the first issue! To good homes! Not to bookstores where they molder forever or get thrown away. Though it's cheaply produced, I think the zine comes out looking nice enough that people want to keep it for its physicality as well as for the ideas.

Actually - at the conference some people asked for 20 copies so they could use it for their classes. I lost my notebook in the conference hotel, and have forgotten who wanted the extra copies. Email me a reminder if you see this post.

One more thing about my little magazine - I would love more suggestions for future poems from any language. It should be relatively short because of the magazine's tiny format. It should be something that you can imagine being translated many different ways into English. And since I don't know every language, I need guest editors to take a look at the quality of submissions! It also helps if the poem is public domain though I don't want to make it a requirement. Put suggestions here in the comments or email them to me!

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

I'm reading an interesting book here on vacation. My father-in-law has a great collection of Korean philosophy, history, psychology, and poetry! Here's a poem from Selected Poems of So Chongju: Translated and with an Introduction by David R. McCann.

The poem in English limps and stumbles. But I feel I can see its beauty through the halting poetics of the translation. Without knowing Korean, without the original poem, and without another version of the poem in English, I still judge the poem. I don't love the translation, and I know that I can't judge the translation's accuracy, but I know I like the poem! How can that be, really? Where is discernment located? How can I trust my perception of the poem through so many imperfect filters?

The poem is from "Collected Poems," 1972.

"Strung out" is probably not meant to sound like a heroin junkie. Or did McCann put in the double meaning on purpose, because the Korean had a double meaning? I'm doubtful!

The last lines, "I am ready now/ to have as they are" doesn't make much sense. I imagine it might be "to have them as they are"; I'm ready now to keep my awareness of my brother's uncertain fate, and these clothes as they are, in an indeterminate state. Couldn't there be a better way to phrase this in English? How frustrating!

"Plain porcelain bowl" is a graceless phrase that brings up unfortunate images of toilets.

From the title, I know it's a rice bowl. I don't know anything about the Yi Dynasty. Perhaps it's very ancient and brings to mind the whole long history of Korea. Perhaps it evokes a particular set of stories about that period, or a certain shape of bowl or glazing style. Later, I'll look it up. For now, I can picture the round bowl with the white laundry, juxtaposed without explanation. The bowl is the poem's title and beginning; it doesn't return: an attractive invitation to read the whole poem again, forcing the reader to ask, "Why a bowl?" It invites circularity. As I thought about this bowl, I realized: The bowl's historical weight, its solidity, its artistry, and its possible status as a valuable art object counterbalances the empty suit of clothes, so ephemeral, personal, mundane. The brothers' separation gives a personal dimension to Korea's political division into North and South. Bowl, clothes left out on the line, and a family torn apart forever. It's very powerful!

I thought of many ways this poem might be written as a terribly bad poem in styles current today. How can the beauty of this poem be destroyed? Made dull, obvious, ham-handed? Imagining this is useful. Then I can avoid those mistakes in my own work.

I enjoyed many other poems by So Chongju, especially the ones from Flower Snake (1941) which mention Verlaine, Baudelaire, and longing to travel to other continents. I dug So's later prose poems, but they are too long to quote here.

Here's another good poem on a difficult subject :

Again, it's in ponderous unpoetic English that can't hide the subtlety of the poem's soul. I admire this poem because it talks about parenting in a way that isn't trite, despite having sunbeams, laughing child, butterfly, all the elements of a Hallmark card, and a doting mother; beyond that, it says something lovely about imagining. Think of mother and child, but also think of poet and poem. As a mother, I imagine my child into being just about as effectively & relentlessly as a baby tries to grab intangible light. So Chongju, here, enjoins the poet to feel a joyous innocence in creation and in striving to write, despite it being impossible to convey the butterfly. Well, that's what I'm seeing!

When I read work like this in translation I feel a keen sense of pleasure mixed with regret for what is missing, and what will always be missing for me. I enjoy trying to see things that are beyond my understanding. I think we have to try as hard as we can to read beyond the particular instance of translation, even if that is an act of hubris...

Looking at a Yi Dynasty Rice Bowl

Seeing this plain porcelain bowl

laundry hung on a line

in the corner of my yard...

white clothes, trousers and blouse

I shall leave unfolded forever.

Like my brother taken

north during the war,

these clothes strung out

like a brother who will never

return,

I am ready now

to have as they are.

The poem in English limps and stumbles. But I feel I can see its beauty through the halting poetics of the translation. Without knowing Korean, without the original poem, and without another version of the poem in English, I still judge the poem. I don't love the translation, and I know that I can't judge the translation's accuracy, but I know I like the poem! How can that be, really? Where is discernment located? How can I trust my perception of the poem through so many imperfect filters?

The poem is from "Collected Poems," 1972.

"Strung out" is probably not meant to sound like a heroin junkie. Or did McCann put in the double meaning on purpose, because the Korean had a double meaning? I'm doubtful!

The last lines, "I am ready now/ to have as they are" doesn't make much sense. I imagine it might be "to have them as they are"; I'm ready now to keep my awareness of my brother's uncertain fate, and these clothes as they are, in an indeterminate state. Couldn't there be a better way to phrase this in English? How frustrating!

"Plain porcelain bowl" is a graceless phrase that brings up unfortunate images of toilets.

From the title, I know it's a rice bowl. I don't know anything about the Yi Dynasty. Perhaps it's very ancient and brings to mind the whole long history of Korea. Perhaps it evokes a particular set of stories about that period, or a certain shape of bowl or glazing style. Later, I'll look it up. For now, I can picture the round bowl with the white laundry, juxtaposed without explanation. The bowl is the poem's title and beginning; it doesn't return: an attractive invitation to read the whole poem again, forcing the reader to ask, "Why a bowl?" It invites circularity. As I thought about this bowl, I realized: The bowl's historical weight, its solidity, its artistry, and its possible status as a valuable art object counterbalances the empty suit of clothes, so ephemeral, personal, mundane. The brothers' separation gives a personal dimension to Korea's political division into North and South. Bowl, clothes left out on the line, and a family torn apart forever. It's very powerful!

I thought of many ways this poem might be written as a terribly bad poem in styles current today. How can the beauty of this poem be destroyed? Made dull, obvious, ham-handed? Imagining this is useful. Then I can avoid those mistakes in my own work.

I enjoyed many other poems by So Chongju, especially the ones from Flower Snake (1941) which mention Verlaine, Baudelaire, and longing to travel to other continents. I dug So's later prose poems, but they are too long to quote here.

Here's another good poem on a difficult subject :

The Child's Dream

In the child's dream a butterfly

has flown away, leaving sunlight behind.

Waking from that dream laughing,

reaching with eyes and cheeks,

the child tries to grasp the sunlight

falling to the floor

from a hole in the paper window.

If mother could be like her child

this way, life would truly be perfect.

Again, it's in ponderous unpoetic English that can't hide the subtlety of the poem's soul. I admire this poem because it talks about parenting in a way that isn't trite, despite having sunbeams, laughing child, butterfly, all the elements of a Hallmark card, and a doting mother; beyond that, it says something lovely about imagining. Think of mother and child, but also think of poet and poem. As a mother, I imagine my child into being just about as effectively & relentlessly as a baby tries to grab intangible light. So Chongju, here, enjoins the poet to feel a joyous innocence in creation and in striving to write, despite it being impossible to convey the butterfly. Well, that's what I'm seeing!

When I read work like this in translation I feel a keen sense of pleasure mixed with regret for what is missing, and what will always be missing for me. I enjoy trying to see things that are beyond my understanding. I think we have to try as hard as we can to read beyond the particular instance of translation, even if that is an act of hubris...

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Guernica, a new magazine

Just heard about Guernica, a new online magazine of art & politics -- apparently they are interested in literary translations.The website is http://www.guernicamag.com.

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Cipher Journal / Juste Lounge / Literal

I recently came across the excellent links page on the excellent on-line journal of translation, Cipher Journal. http://www.cipherjournal.com I highly recommend it -- and by the way, for those new to blogging, it includes a nice list of literary translation blogs. (Well, who isn't new to blogging except maybe ALTA's own treasure, Liz Henry?)

On another note, I just came home from a bilingual poetry reading in the new Juste Lounge Poetry Series in Bethesda MD (a suburb of Washington DC). It featured myself, Yvette Neisser (who also runs the Cafe Muse Poetry Reading Series), Maritza Rivera Cohen, and Luis Alberto Ambroggio. All poets, all Spanish / English translators, plus we had an open mike and got some German poetry in fine translation by Paul Hopper and also some Rumanian poetry. Alas, the name of the Rumanian poet and translator both escape me -- but they were great. All three of the featured readers -- to our mutual suprise -- read poems from Robert Giron's recent anthology, Poetic Voices Without Borders. Robert Giron's publishing house is www.givalpress.com --- a site that may be of interest to many translators.

Here's something fun for those of you going to Guadalajara for the annual book fair: Rose Mary Salum, founding editor of the bilingual journal Literal: Latin American Voices (www.literalmagazine.com) will be presenting the new issue dedicated to Peru at 5 p.m. on Thursday December 1st (Salon Jose Luis Martinez, del Centro de Negocios, Expo Guadalajara).

On another note, I just came home from a bilingual poetry reading in the new Juste Lounge Poetry Series in Bethesda MD (a suburb of Washington DC). It featured myself, Yvette Neisser (who also runs the Cafe Muse Poetry Reading Series), Maritza Rivera Cohen, and Luis Alberto Ambroggio. All poets, all Spanish / English translators, plus we had an open mike and got some German poetry in fine translation by Paul Hopper and also some Rumanian poetry. Alas, the name of the Rumanian poet and translator both escape me -- but they were great. All three of the featured readers -- to our mutual suprise -- read poems from Robert Giron's recent anthology, Poetic Voices Without Borders. Robert Giron's publishing house is www.givalpress.com --- a site that may be of interest to many translators.

Here's something fun for those of you going to Guadalajara for the annual book fair: Rose Mary Salum, founding editor of the bilingual journal Literal: Latin American Voices (www.literalmagazine.com) will be presenting the new issue dedicated to Peru at 5 p.m. on Thursday December 1st (Salon Jose Luis Martinez, del Centro de Negocios, Expo Guadalajara).

Surviving the ATA as a Literary Translator

I've just survived the ATA, the American Translators Association blowout conference, as a first-time attendee and one of the ALTA-table ALTA promoters.

Survival is the word. After the relatively calm environment of Montreal, I was plunged into a world of vendors, balloons, seminars, techies, and in addition to all of the above, gave a talk about Swedish Literary translation at one of the Nordic division events.

While manning the ALTA table (womanning the ALTA table?), I met three sorts of people: Those who have tried literary translation and decided to make some money doing something else, those who are terrified to attempt literary translation ("much more difficult than tech"), and those who wanted to join ALTA and do literary translation as a sideline, knowing that they would be translating literature for fun and not profit.

By far, the largest number of people I met at this just-concluded ATA conference fell into the first category. Many of them have given up literary translation entirely, citing that they were losing money and had to earn a living somehow.

What does it say for our country that literary translators cannot make a living as literary translators? Do you know anyone making a living at literary translation? As far as I can tell, pretty much everyone has another line of work, whether it is academia, academia, academia, graduate school, private wealth to distribute, or cashier at the local independant bookstore.

In effect, the academic world is subsidizing the field of literary translation (correct me if I'm wrong!) and those who have not secured academic positions cannot continue for long in the field. Also (again correct me if I'm wrong), a great academic may or may not be a great literary translator (although many are). A great literary translator may not be a great academic...you get the drift.

So the question I'm pondering this week is...is making a living too much for a literary translator to ask for?

Meanwhile, any bookstores looking for cashiers this holiday season?

Survival is the word. After the relatively calm environment of Montreal, I was plunged into a world of vendors, balloons, seminars, techies, and in addition to all of the above, gave a talk about Swedish Literary translation at one of the Nordic division events.

While manning the ALTA table (womanning the ALTA table?), I met three sorts of people: Those who have tried literary translation and decided to make some money doing something else, those who are terrified to attempt literary translation ("much more difficult than tech"), and those who wanted to join ALTA and do literary translation as a sideline, knowing that they would be translating literature for fun and not profit.

By far, the largest number of people I met at this just-concluded ATA conference fell into the first category. Many of them have given up literary translation entirely, citing that they were losing money and had to earn a living somehow.

What does it say for our country that literary translators cannot make a living as literary translators? Do you know anyone making a living at literary translation? As far as I can tell, pretty much everyone has another line of work, whether it is academia, academia, academia, graduate school, private wealth to distribute, or cashier at the local independant bookstore.

In effect, the academic world is subsidizing the field of literary translation (correct me if I'm wrong!) and those who have not secured academic positions cannot continue for long in the field. Also (again correct me if I'm wrong), a great academic may or may not be a great literary translator (although many are). A great literary translator may not be a great academic...you get the drift.

So the question I'm pondering this week is...is making a living too much for a literary translator to ask for?

Meanwhile, any bookstores looking for cashiers this holiday season?

Facets of Sappho

The Sappho Companion is a perfect book for any translator, critic, or poet. It is a historical overview of what people have been saying about Sappho since her own lifetime. I learned quite a lot about literary fads and myths.

For example, in her own lifetime, critical emphasis was sometimes on the greatness of her poetry, sometimes on her status as a poet relative to other women poets. After her death, for hundreds of years Sappho was written into plays, and the myth of "Sappho's leap" arose, the idea that for unrequited love of Phaon, she lept off the Leucadian cliffs into the sea. Reynolds and other scholars claim that Phaon was actually another name for Adonis, and Sappho wasn't necessarily writing of her personal love for a guy named Phaon, and there is no evidence for a suicidal leap. That came later, in Greek comedies and tragedies about her life.

Reynolds also delves into concepts of Sappho as teacher, as lesbian, as bi, as a poet overcome by passion, as "chaste", as cautionary tale about the dangers of love and writing, as representative of "the New Woman"; until it becomes clear that at different times and in different countries, what anyone at all means by referring to "Sappho" is amazingly variable. Each chapter covers references to Sappho during a particular place and time, thick with examples. At the end of each chapter there are long excerpts from poems, novels, and plays. I loved this format, as it allowed for deeper understanding of the texts under discussion without the tedium of footnotes. (And as a side note: here's a cool link to a page with 26 different translations of Sappho's jealousy/passion poem, the one Barnard translates as "He is more than a hero/he's a god in my eyes...")

Why is this important for translators? It is a beautiful example of how translation of Sappho's work changed over time. But not only that. In my own work, for example, translating 19th and early 20th century women poets, it's hugely important for me to realize that their references to Sappho or to elements of the Sappho mythos are different from my personal concept of Sappho. In other words, I came to Sappho from a combination perspective of the Mary Barnard translations and 70s lesbian feminist interpretations! And that's not the same Sappho that Mercedes Matamoros is writing about in her 1902 book El último amor de Safo. Matamoros was a Cuban poet and a translator of Byron, Chenier, Goethe, Schiller, and others; she was part of a literary circle that included many women writers such as Aurelia Castillo, Nieves Xenes and her sisters, Luisa Pérez de Zambrana, and Gertrudis Gó de Avellaneda. What Margaret Reynolds' book did for me is to underscore the importance of figuring out historical context from the examples I can find, and the danger of making assumptions! I'm keeping that firmly in mind as I translate Matamoros's Sappho poem cycle. I also look to other poem-cycles on Sappho and Phaon, like Mary Robinson's from 1796. I can't prove that Matamoros read it, but it's good background anyway as it seems likely she would have read something similar to pick up her Sappho mythos.

For example, in her own lifetime, critical emphasis was sometimes on the greatness of her poetry, sometimes on her status as a poet relative to other women poets. After her death, for hundreds of years Sappho was written into plays, and the myth of "Sappho's leap" arose, the idea that for unrequited love of Phaon, she lept off the Leucadian cliffs into the sea. Reynolds and other scholars claim that Phaon was actually another name for Adonis, and Sappho wasn't necessarily writing of her personal love for a guy named Phaon, and there is no evidence for a suicidal leap. That came later, in Greek comedies and tragedies about her life.

Reynolds also delves into concepts of Sappho as teacher, as lesbian, as bi, as a poet overcome by passion, as "chaste", as cautionary tale about the dangers of love and writing, as representative of "the New Woman"; until it becomes clear that at different times and in different countries, what anyone at all means by referring to "Sappho" is amazingly variable. Each chapter covers references to Sappho during a particular place and time, thick with examples. At the end of each chapter there are long excerpts from poems, novels, and plays. I loved this format, as it allowed for deeper understanding of the texts under discussion without the tedium of footnotes. (And as a side note: here's a cool link to a page with 26 different translations of Sappho's jealousy/passion poem, the one Barnard translates as "He is more than a hero/he's a god in my eyes...")

Why is this important for translators? It is a beautiful example of how translation of Sappho's work changed over time. But not only that. In my own work, for example, translating 19th and early 20th century women poets, it's hugely important for me to realize that their references to Sappho or to elements of the Sappho mythos are different from my personal concept of Sappho. In other words, I came to Sappho from a combination perspective of the Mary Barnard translations and 70s lesbian feminist interpretations! And that's not the same Sappho that Mercedes Matamoros is writing about in her 1902 book El último amor de Safo. Matamoros was a Cuban poet and a translator of Byron, Chenier, Goethe, Schiller, and others; she was part of a literary circle that included many women writers such as Aurelia Castillo, Nieves Xenes and her sisters, Luisa Pérez de Zambrana, and Gertrudis Gó de Avellaneda. What Margaret Reynolds' book did for me is to underscore the importance of figuring out historical context from the examples I can find, and the danger of making assumptions! I'm keeping that firmly in mind as I translate Matamoros's Sappho poem cycle. I also look to other poem-cycles on Sappho and Phaon, like Mary Robinson's from 1796. I can't prove that Matamoros read it, but it's good background anyway as it seems likely she would have read something similar to pick up her Sappho mythos.

Saturday, November 12, 2005

The Ethics of Translation

The Translation/Transnation series put out by Princeton University Press focuses on the interrelation of language, literature and nation in global--or "transnational"--age. All of these texts are worth a close reading. The most recent publication in this series, Nation, Language, and the Ethics of Translation, edited by Sandra Bermann and Michael Wood (both of whom are at Princeton), explores the status and role of translation in more global cultural markets, touching on the impact of new technologies on translation and the move of translation from its "home" in the humanities to more interdisciplinary, academic contexts. The following passage from the introduction provides an apt summary of this project:

[If] language and translation have become increasingly important in national and international relations, and in the processes of "globalization" more generally, their role as cultural as well as linguistic entities is only beginning to be theorized. The social sciences, that have so well described our political, economic, military, and information networks, have, for the most part, ignored these issues or considered them simply a necessary interface. This is most likely because, in their very texture, these linguistic matters belong so fully to what we traditionally think of as the humanities. Yet closely considered, language and translation in fact open up the unavoidable complexities, the historically ingrained problems and prejudices, and the intense day-to-day negotiations that occupy our interwoven global communities, setting into stark relief the difficult suturing of global networks and the over-stressed joints of the international body politic. They tend to raise questions about linguistic power and the dissemination of texts in various media; they bring to the fore issues of human rights as well as intellectual property; they also illuminate disparities among states, nations, and local traditions, and the often tragic problems of linguistic and cultural diasporas; they reveal complex multiplicities in the shadow of apparent unity.I haven't made my way through all of these essays so I can't provide a balanced review of this collection, but I think that it raises important questions for the future of translation studies in academia. Translation in most academic programs is still relegated to a humanities pursuit, but I would be interested to know of programs that address translation issues within interdisciplinary frameworks and how this this kind of approach is accomplished.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Nerds and nard

"Nardo" is a word that I just never see outside of Spanish or Latin American poetry. It gets translated as "nard" or "spikenard". What the heck is nard? I've been wondering for over 20 years. From context, it's obviously a white flower, heavily scented. I read in the Wikipedia that it is a variety of valerian, a soporific. But it also sometimes appears to be a sort of smelly lotion; unguent, oil, or balm, scented with that flower's scent. It's mentioned in the Bible in the Songs of Solomon, and again when Mary Magdalene gave Jesus a fancy perfumed footrub.

In poems, it often has erotic and religious undertones. But I've also wondered if it is associated with death as well as sleep; if it is in flower or is used in perfume form in wakes and funerals. The context is of a sexy, morbid, funereal splendor and perhaps of a heavy overpowering incense. In fact I think it might be a common flavor of incense. It's the sort of thing that a hero of an H. Rider Haggard novel would be drugged by as he goes into Ayesha's secret temple. García Lorca seemed fond of it; it's all over his poems.

The US English-speaking reader isn't going to have the faintest clue what nard is. Here is a perfect place to choose domesticizing over foreignization. I've translated it differently in different poems. "Scented lily?" "Costly balm?" I've translated it as "myrrh" but am not entirely happy with that. "Fragrant valerian?" "Holy patchouli"? (That's a joke.)

For example, here in "Insomnia" by Juana de Ibarbourou, we run into some nard:

What are those varas de nardo? I thought they could be withered stalks of the flower, but also they might be crumbling sticks of incense. Maybe it is obvious to a Catholic Spanish-American. If so, I'd love to know!

My point is really that I've seen a lot of translators interpret it by a dictionary definition without thinking about it or digging deeper, and without trying to make the meaning of the flower/unguent/incense apparent to their readers.

Untranslated and unexplained, I think "nard" in a poem makes that poem fall flat in English.

In poems, it often has erotic and religious undertones. But I've also wondered if it is associated with death as well as sleep; if it is in flower or is used in perfume form in wakes and funerals. The context is of a sexy, morbid, funereal splendor and perhaps of a heavy overpowering incense. In fact I think it might be a common flavor of incense. It's the sort of thing that a hero of an H. Rider Haggard novel would be drugged by as he goes into Ayesha's secret temple. García Lorca seemed fond of it; it's all over his poems.

The US English-speaking reader isn't going to have the faintest clue what nard is. Here is a perfect place to choose domesticizing over foreignization. I've translated it differently in different poems. "Scented lily?" "Costly balm?" I've translated it as "myrrh" but am not entirely happy with that. "Fragrant valerian?" "Holy patchouli"? (That's a joke.)

For example, here in "Insomnia" by Juana de Ibarbourou, we run into some nard:

En un zumo de lirios morados

Se anegan mis ojos sombríos y largos

Y en un zumo amarillo de cera

O de vara de nardo marchita,

Se han ahogado las llamas rosadas

Que coloran la piel de mis labios.

What are those varas de nardo? I thought they could be withered stalks of the flower, but also they might be crumbling sticks of incense. Maybe it is obvious to a Catholic Spanish-American. If so, I'd love to know!

My point is really that I've seen a lot of translators interpret it by a dictionary definition without thinking about it or digging deeper, and without trying to make the meaning of the flower/unguent/incense apparent to their readers.

Untranslated and unexplained, I think "nard" in a poem makes that poem fall flat in English.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Translation Wars

Run--do not walk--to your local library or newsstand for the current issue of the New Yorker and turn to the Onward and Upward with the Arts essay: "The Translation Wars: How the race to translate Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky continues to spark feuds, end friendships, and create small fortunes," by editor-in-chief David Remnick. Remnick trashes Constance Garnett, about whom the salient fact is that she engendered a deep love of Russian literature among generations of English-language readers, and parrots the received (though not by many people who are specialists in the field) wisdom about the Pevear/Volokhonsky team being the best thing to happen to Russian literature since sliced bread. (They're not.) I'm still in the middle of the article myself but want to encourage people to rush off and find a copy before the next issue supplants it.

Thursday, November 03, 2005

This blog's purpose

I'm envisioning this blog as a place for public discussion of translation. In it, members of ALTA, the American Literary Translators Association, will post a few times a week about:

- their own thoughts on translation

- particular translation problems, process

- copyright and publishing issues

- literary gossip

- book reviews relevant to literary translation

- grants, awards, calls for submission

- other good stuff I haven't thought of

This isn't meant to take the place of the newsletter; it is more like a syndicated column split between several authors; blog posts can be short and to the point, or long and more personal or chatty.

- their own thoughts on translation

- particular translation problems, process

- copyright and publishing issues

- literary gossip

- book reviews relevant to literary translation

- grants, awards, calls for submission

- other good stuff I haven't thought of

This isn't meant to take the place of the newsletter; it is more like a syndicated column split between several authors; blog posts can be short and to the point, or long and more personal or chatty.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)